Back Home and Processing

I'm feeling the effects of a 36 hour Monday and only 4 hours of sleep now. This is going to be just like the first night in Saigon when I totally died in bed at 5 p.m.. Before I do, I'll try to get down some of the things going through my mind today and the people I've talked to so far on my continuing quest to reconnect with Asia.

Not to evoke cliché, but it does all feel like a dream. I've always felt some kind of magical connection with speaking languages other than English, starting with a one month trip to Spain the summer after high school graduation.

Until then I didn't really think I was that much of a linguist. I had forgotten all my Taiwanese and Mandarin just a few years after we returned to the US. Then I took high school Spanish which involved vocabulary tests and other tedium resulting in a lot of mediocre "C"s and "B"s.

I had a real talent for English, though, and worked in student journalism eventually landing the co-editor position at the Bismarck High School High Herald my senior year. Man, I sucked at that! I've never seen my parents more upset and disappointed in me. Everyone including me knew I was smarter than that but I just didn't want to do it.

Finally, high school was over and I had the one month trip to Spain all planned out. Mom coordinated a foreign exchange program called Nacel and that was the organization I went through for the trip.

I fancied myself a world traveler already at that age. Hey, I lived in Taiwan as a kid, so Spain should be no big deal, right? On the plane ride over I puffed myself up with all sorts of snobbish pride in my superior internationalism. What I discovered in Spain was extraordinary, though.

It was so foreign. Everything there was unfamiliar from the people to the cars to the smells and even the dirt. The damn dirt didn't look like anything I'd seen, for cryin' out loud! So much for Chris the World Traveler; I was dumbfounded by terra incognita in the most literal way.

The language was also a major challenge for the first week or two. There goes another shot to my ego: ooh, I could speak Chinese as a kid, Spanish will be like faking a British accent ... if only these damn Spaniards would slow down and annunciate for a second, maybe I could understand them!

By the end of the month, though, I was rockin' the fluency. My vocabulary needed a lot of fleshing out and my comprehension still sucked but man could I roll my double "r"s and hit the vowels with perfect pitch like a newly-tuned guitar. I perused a minor in Spanish in college only to find more boring, book-learning tedium. My vocabulary improved, but of what use is Spanish, anyway?

I considered a degree in linguistics, still under the illusion that somewhere in me was an amazing multi-lingual superhero just waiting to be unleashed. I took a whole year of French and then lost interest. I did learn more French speaking with the exchange students that came to North Dakota through Mom's Nacel program, though. That was fun.

Once I finally moved out of my parents house to go to Moorhead State University in Moorhead, MN I discovered they had Mandarin classes. Cool! Here was my chance to redeem myself! All I had to do was start taking Mandarin classes and one night my brain would go "snap!" and I'd be fluent again because it would all just come back to me; easy as that.

Two years later I proved, again, that I could get the tones and pronunciation right, but that mind-numbing tedium of book-learned vocabulary bit me in the ass once more.

I graduated, entered the working world and every now and then mentioned that I spoke Spanish, French and Chinese in descending order of proficiency on job applications. I took a couple Spanish-speaking calls when I worked customer service at Digital River, but that's all my tedious years of quadralingual education got me.

I floundered. Worked as a Web programmer and found it all even more tedious than vocabulary tests. I got in trouble for slacking off on the job, came close to getting fired a couple of times and then finally snapped myself out of it and got help.

About a year ago exactly I started working for WUGNET Publications, a very small company based out of Media, PA. They're a work-from-home operation and that's what I do now: general operations management of Web sites, mail servers, RSS feeds and anything else techie. It's a great job and I love it.

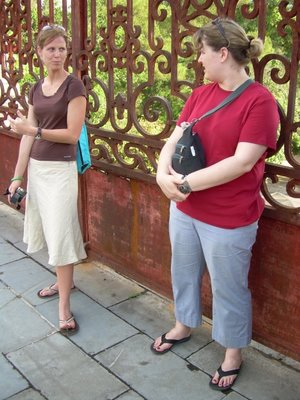

The job allows a great deal of flexibility, as you can imagine. One of the results of that flexibility was being able to join Reese on this trip to Viet Nam. Just take the laptop with me and I can work wherever there's a wireless coffee shop. Next time around there are some technical glitches I want to work out such as making my cell phone compatible with the Asian network, but all-in-all it worked out pretty well.

This trip was supposed to be a fun getaway with the wife and an opportunity to discover a country few Americans know much about anymore. Mom kept asking me if I was going to try to learn any Vietnamese before the trip. I more or less dodged the question. No reason to get anyone’s hopes up about my language skills. As always, I’ll probably be able to pronounce things great, but without a fleshed-out vocabulary what good is it?

Plus, two weeks is far too short a time to learn anything more than “Hello,” “Good bye,” “Thank you” and “You’re welcome.” No, I was looking forward to feeling in Vietnam the same way I felt in Spain 15 years ago: totally foreign experience rife with culture shock.

I got over the culture shock after the first day. That’s when something new started happening: waves and waves of emotion and memory coming back to me. I hadn’t forgotten anything about Taiwan, mind you, I just didn’t think about it very much:

I only lived there for three years. The other 30 years of my life have been in America, so that’s 100% who I am: American. Sure, I’ve been places and studied languages. I’m even pretty good at it. Big deal; anybody can say “Ni hao” with the proper tones if they try.

All those defenses I’d had up for 27 years to protect myself from being teased by the other American kids started breaking down. My chest was no longer puffed up with the normal American ego façade. I started automatically holding my hands at my sides, bowing my head lightly at people and smiling more.

Until that point I kept bugging Ashley, the Vietnamese-American of our group, with “how do you say ‘good bye,’ again?” several times until I remembered it. Once I let go and opened up I started learning Vietnamese at an exponential rate. After a couple of days I was constantly at Phong’s ear, asking him how to say this or how to say that. A week into the trip I was desperately searching for English-Vietamese dictionaries or phrase books.

I finally got a phrase book the first morning in Ha Noi and hungrily flipped through it looking for nouns and verbs I lacked. I tried every new phrase or sentence out numerous times on any Vietnamese friendly enough to listen. I started constructing new sentences out of words, phrases and sentences I already knew.

The memories and emotions started hitting me like a typhoon. I sat and watched hours of Chinese TV, picking up words and phrases here and there and either remembering what they meant or recognizing them but not remembering the meaning.

About this time Tim noticed I was more quiet than normal. The first week I went out with he and some of the others to party and drink. Now I went to bed at a reasonable time, got up at the crack of dawn and buried my nose in my new little phrasebook.

I began to finally understand. On bus rides to tourist traps I’d watch women in conical hats harvest rice and choke back tears. Everywhere I looked something made me feel like a kid. A couple of times I fantasized about returning to Taiwan, visiting Hai Ou, having people recognize who I am and I’d have to stop for fear of crying like a baby in front of the rest of the tour group. I wandered the night market with Long and told him to only speak Vietnamese to me and felt my American self totally and magically disappear for an hour or two.

Then I spoke with Ashley and commiserated about her childhood as an Asian-American. She was teased as a kid for being different and now her friends and family in Viet Nam say she’s got a wall up around her all the time. She doesn’t open up like they do. Holy shit, can you blame her?

I told her I felt silly for saying so, but I knew exactly what she meant. I got teased for having a funny accent and speaking very little English in 1-3 grades. I did my 1st grade math homework in Chinese. “Hey, say something in Japanese!” kids often teased me. I made it worse by correcting them: “I speak Taiwanese, not Japanese!”

This coming from a kid with hair so bleached blonde from the Taiwan sun it was almost white.

Bottle it up. Don’t speak Taiwanese. Speak English so the girls will like you and the boys won’t beat you up. Put up a wall. Forget Taiwanese and Chinese. They don’t want that here.

I got so good at being American I forgot who I was. I believed what everyone else told me that being different was bad. Be just like everyone else. Don’t pronounce Spanish perfectly, screw it up. Don’t talk to that Asian co-worker about Asia, they’ll think you’re secretly racist and trying to cover it up. Don’t tell your white co-workers you lived in Taiwan or that you speak other languages, they’ll assume you’re being boastful or condescending. Act as nonchalant as possible when someone else outs your Taiwanese past. It’s not that interesting. No, I don’t think your childhood was boring compared to mine. I just lived there, who cares? Let’s talk about sports instead or the fucking weather. Let’s talk about anything, anything at all as long as we don’t talk about Taiwan. Please? Please stop!

Woah. OK. Back to writing after a cathartic, 5 minute cry that last paragraph envoked. Don’t know if I should continue from there or not. I just never realized how painful it’s been for me to feel so profoundly disconnected from what turns out to be a significant part of my childhood. These last two weeks I’ve felt more mature, purposeful, capable and connected than I can remember. I’ve also cried enough to make some employee of Kleenex very rich.

Two nights before we were due to fly back home I started feeling depressed. I fell in love with Viet Nam. I could smile at anyone on the street, nod and say “Xin chao” and expect the same in return. Things here were possible and when I spoke Vietnamese, bowed my head or lit a bundle of incense at the temple nobody looked at me funny. Nobody thought I was some pretentious westerner faking he’s Asian. One of the women at the juice and coffee bar at the Ha Noi hotel asked me if I lived in Saigon because of my accent.

When I tried to pray with a bundle of incense Saturday morning I had trouble getting the sticks lit. A middle-aged Vietnamese woman next to me gently grabbed my hand and pointed the sticks down into one of the flaming bits of paper. She spoke Vietnamese to me as if she knew I didn’t want to hear English. I responded with a very gracious “Cam u’n ngyun.” but quietly. Once they were lit she motioned for me to shake the flames out so the incense would smoke. I did so, thanked her again and walked slowly to the altar.

I held the bundle in the lotus position and prayed. All I said was “Thank you, xie xie, cam u’n …” two or three times and then stuck the bundle upright in the pot. I don’t remember the phrase in Taiwanese anymore but once I relearn I’ll be sure to add it to the prayer.

Then I sat and meditated by the lake. I just noticed words popping into my head and let them fall into an abyss. Some were English, some Mandarin and some Vietnamese. I’m a beginner when it comes to meditation, so I did it for maybe 5 minutes before deciding to move on. I walked slowly around the lake, hands held behind my back. I thought about an earlier wish, that I wanted to be buried in Hai Ou. I was so happy to think about that I almost teared up yet again.

I’ve never felt that way about dying before, just the bleak, existential pull to the abyss. For the first time I thought about dying, being laid to rest near the black sand beaches of Hai Ou, just over the dike near the new ICA building where the preschool used to be. For the first time I thought it’d be OK to die, and I’d be ready and happy to go and rest there. Things would be complete so I wouldn’t have to worry.

So, yes, I don’t mind saying it now. I’m an Asian-American. My name is Chris Druckenmiller and I am from Solen, ND where I learned to be sad. Wo jiao Teng Ke Wu hai who shi de Hai Ou, Taiwan zai wo gao xing.

This morning my parents told me that Ke Wu is a kid’s name. Apparently I’m overdue for a grown-up name.